The United States economy is widely expected to slow in the next few quarters. Last Friday's government reports gave some insights on how this slowdown might affect corporate earnings. Developments in China may also have an impact.

According to a recent report from Standard & Poor's, earnings for S&P 500 companies are now expected to be 13.2 percent higher in 2006 than in the previous year. Reasons for the strong earnings growth include healthy global economic growth and improved pricing and cost controls.

Will these conditions persist? Last Friday's US government data provided some clues.

The focus of most analysts' attention on Friday was the retail sales report from the Commerce Department, not surprisingly since consumer spending contributes about 70 percent of US gross domestic product. The report showed that retail sales rose 1.4 percent in July, more than economists had expected.

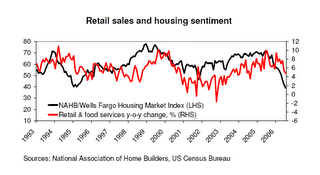

While this looks good, the monthly growth rates tend to be volatile. Perhaps more significantly, sales were up only 4.8 percent compared to July 2005. This is well down from the rate of almost ten percent a year ago, and the year-on-year growth rate appears to be on a downtrend, as the following chart shows.

With the National Association of Home Builders/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index continuing to fall in July, retail sales are likely to deteriorate further over the following months.

Meanwhile, pricing power is likely to be maintained or even rise, given the inflationary environment of today. The question is whether costs can be contained at the same time.

Last Monday, at InvestorsInsight, John Mauldin reproduced a report from Louis-Vincent Gave, a partner at GaveKal Research. The report says that because of its need to create jobs, China keeps expanding manufacturing capacity and thus exerts "relentless downward pressure on manufactured prices". This in turn creates "more leeway for other prices in the world economy to go up".

As a whole, this is good news for businesses elsewhere; they get better pricing power and lower costs at the same time, provided, of course, that they are not competing against the Chinese manufacturers.

The report does not explicitly say it but obviously lower costs for businesses include lower labour prices. Labour loses pricing power, especially the type of labour that competes with China, and becomes vulnerable during a slowdown.

In contrast, Gave thinks that in a slowdown, corporate profit margins would fall but "may be much higher than some expect".

Whether Gave proves right depends to a considerable extent on whether China is continuing to expand manufacturing capacity enough to put downward pressure on its export prices and produce a deflationary impact on the rest of the world.

Note that such an impact would not only reduce input costs for businesses in other countries but could also keep monetary policies around the world more accommodative than would otherwise be the case and thus support economic growth. Remember that the Federal Reserve in particular includes the contribution of Chinese prices on inflation but excludes the direct contribution of energy prices, which are among those "other prices" that Gave says tend to go up.

To determine the trend of China's prices, Gave looked at Hong Kong's re-export price index as a proxy for the price of Chinese exports. He showed that Chinese export prices fell in 2001 and 2002, triggering the deflation scare of the latter year, but rose thereafter, especially in 2004 and 2005. Then it started to slow again in 2006.

Unfortunately, the data presented in the report reproduced by Mauldin appears to have ended in March. The latest available data from Hong Kong's Census and Statistics Department show that this index started to turn up again in March, and continued rising in April and May.

This trend is corroborated by brokerage and investment bank CLSA's survey of purchasing managers in China. In his comments on the July survey, Eric Fishwick, Deputy Chief Economist at CLSA said: "For the fourth month both input and output price indices were above the 50 breakeven line signaling that businessmen have no choice but to try and pass input price rises on. The era of China 'exporting deflation' is long over."

Not so fast.

Friday also saw the US Labor Department release its report on import and export price indexes. The overall import price index rose 0.9 percent, but this was boosted by petroleum. The import price index excluding petroleum fell 0.1 percent.

More specifically, the import price index for China fell 0.2 percent in July. Compared to the previous year, this index is down 1.3 percent.

If China's export prices are rising, it is not yet showing up in the US data. Or perhaps China is only exporting deflation to the US.

So the trend is not exactly clear, but if China does keep exporting deflation at the same time that the US economy weakens, US corporate profits might hold up better than in the average downturn even as the US job market collapses. As Gave puts it, China gets the jobs, America gets the profits.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Blog Archive

-

▼

2006

(305)

-

▼

August

(26)

- US and Japan see slowing, others looking at more t...

- Fed releases minutes, mixed news on the consumer

- Eurozone money supply growth slows

- US housing market weakens, will the stock market f...

- Inflation tame in Japan and Germany

- More data pointing to slowdown

- US existing home sales, Japanese trade surplus fall

- Fed may hike again, but signs of slowdown spreadin...

- UK house prices fall, impact of falling US housing...

- More signs of slowdown and inflation, China raises...

- US mixed, Europe cools

- US core inflation and other indicators slow

- Getting cooler

- Slowdown seen in the US, still hot elsewhere

- What US retail sales and import price trends mean ...

- Slowdown moves to Japan, leaves the US

- Trade and interest rate trends persist

- Fed may stop, others may not

- Fed pauses

- US consumer credit rises, UK and Japanese economic...

- Markets signalling slowdown in US economy

- US job growth and other data reinforce slowdown ex...

- ECB and BoE raise rates, Fed next?

- More signs of US slowdown, rates still likely to r...

- Mixed US data, hotter elsewhere

- Fed rate hikes "tricky", ECB less so

-

▼

August

(26)

No comments:

Post a Comment