A few weeks back, stock and bond prices had been rising on hopes for an imminent interest rate cut in the United States. Those hopes have largely evaporated and over the past week or so, bond prices have fallen. However stock prices continue to go up, this time on renewed optimism on the economy.

Last week saw many stock markets around the world hit multi-year and even all-time highs.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at a record 11,960.51 on Friday. Some smaller markets achieved the same feat. Singapore's Straits Times Index closed at a record 2,666.68 on Friday. The Swiss SMI hit a record 8,673.7 on Thursday, although it fell back a bit on Friday.

Emerging markets were not left out. India's Sensitive Index rose to a record 12,736.42 on Friday.

Other markets hit multi-year highs. The pan-European FTSEurofirst 300 index closed at a five-year high of 1,440.8 on Friday, with the FTSE 100 closing at 6,157.3, its highest close since February 2001. Hong Kong's Hang Seng Index closed at 17,988.86 on Friday, its highest close since March 2000.

Stock markets have been boosted by reports suggesting that the global economy and, especially, the US economy, is not slowing as dramatically as some feared. For example, on Friday, the Commerce Department reported that although US retail sales fell 0.4 percent in September, retail sales excluding gasoline rose 0.6 percent. In addition, the University of Michigan said its index of consumer sentiment rose to 92.3 this month, the highest since July 2005, from 85.4 in September.

Fixed income investors finally seem to agree with this assessment of the economy, as indicated by a recent rise in bond yields, reversing earlier falls. No doubt, indications from the Federal Reserve -- from the last Federal Open Market Committee meeting minutes and from recent speeches by Fed officials -- that it remains concerned about inflation were also taken into consideration by the market.

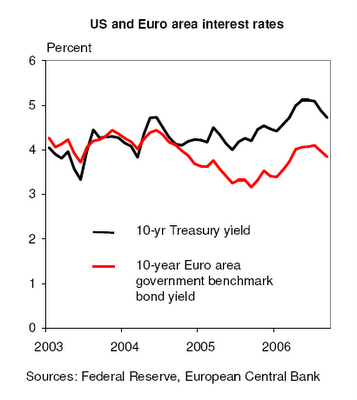

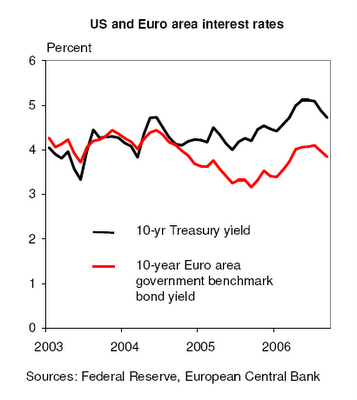

Last week, the yield on the benchmark 10-year US Treasury note rose 10 basis points to 4.80 percent, the highest since 19 September. In Europe, government bonds fell for a third week last week, the yield on the German ten-year note rising 7 basis points to 3.83 percent.

What is interesting about the recent market movements is that while bond prices have reversed in recent weeks on the changed outlook, stocks have maintained their direction of movement: up. When the economy looked to be weakening, some took it as a signal of impending rate cuts by the Federal Reserve -- a good thing for stocks. With the economy looking more resilient now, some are taking it as implying better earnings prospects -- a good thing for stocks.

I am not sure whether that is irrational or just exuberance, but such thinking should cause investors to question what exactly is driving this market.

What does seem important to the market, in my opinion, is that, the recent rise in yields notwithstanding and despite all the rate hikes by the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) over the past few years, bond yields remain relatively low. In fact, the 10-year Treasury note is currently yielding about the same as it did around the middle of 2004, when the Federal Reserve started hiking interest rates. Yields on euro zone government bonds are even lower than they were then and not much above where they were at the end of 2005 when the ECB started its rate hike cycle.

If interest rates that were around current levels or even higher in 2004 could not stop the bull market then, it is quite reasonable to suspect that they might not be able to stop it now either.

So why have interest rates been persistently low? At a conference in Canada on 6 October, former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan suggested that global integration is the reason.

According to a report in the Financial Times, Mr Greenspan said that the collapse of Communism in eastern Europe and the shift towards more market-based economies in China and other parts of the developing world increased the global labour supply and "brought disinflation and lowered inflation risk premiums and long-term interest rates, creating a decline in real interest rates and equity-risk premiums". As a consequence, "the real market value of assets increased faster than GDP".

Apparently things have not changed much recently. The US trade deficit, a reflection of global integration -- especially the integration of China -- continued to rise in August to a record US$69.9 billion. China's trade surplus also hit a high in August, and exports continued to grow in September.

And the disinflationary impact of trade persists, with prices of imports into the US rising just 2 percent in the 12 months to September, and that is inclusive of oil imports. Non-petroleum import prices rose just 0.1 percent in September.

Mr Greenspan also said that the tightening cycle from 1994 to 1995 was "highly disruptive" but failed to rein in stock prices. "We didn't diffuse the bubble, we made it worse," he said. "The stock market was flat during the tightening period and when the tightening ended in 1995 the stock market took off."

So far, that episode seems to be repeating itself this year. Global stock markets were indeed highly disrupted around May and June when all the major central banks were tightening monetary policy in synchrony. When the Federal Reserve paused in August, stock markets took off.

Then again, it may be too soon to conclude since the tightening cycle may not be over yet. Neither the Federal Reserve nor the ECB have given clear signals that rate hikes are at end. In fact, the ECB is expected to hike rates further, while even the Federal Reserve has made it clear that if it moves at all, it is more likely to hike than to cut.

So with bond yields already rising once again, stock investors would do well to keep a close watch on the actions of central banks and interest rates.